South East Asian countries are depicted with plastic polluted beaches, plastic waste on the curbsides, and marine animals washed up on shore with plastics found in their stomachs. However, a closer look at the waste sector of specific cities and municipalities in some countries reveals a remarkable zero waste movement. This article embarks on an exploration of the zero waste approach and discusses its feasibilityfor Cambodia.

The Zero Waste Approach

The zero waste approach is a set of practices aimed at minimizing waste at the source. The core principles are waste prevention, reuse, recycling, and composting to divert materials from landfills (Awasthi et al. 2021). It encourages a circular economy where resources are used efficiently and sustainably, and the lifecycle of products is considered from production to disposal. The term evolved in the 1990s with the awareness of acknowledging that land is not (?) endless and nobody wants to live on landfill. However, it means more than “just” use the waste as a valued resource, some researchers describe it as a philosophy, a lifestyle, requiring a collective effort from all in order to achieve a cultural and economic shift that challenges the prevailing linear model of consumption and disposal (Permana et al. 2022). It must include all spheres of society: e.g. business needs to be open for new business models, focusing on circular economy strategies; the government needs to integrate circular economy in their national policy, and most importantly it needs to include the communities in the entire process; research must focus on recycling management infrastructure, its potential benefits, and consumer behavior or behavioral interventions; last but not least, consumers must start to separate their waste properly and adopt environmentally friendly behaviors (Awasthi et al. 2021). The zero waste approach is holistic and therefore very complex. There are already some countries that have 100% waste recycling or countries with very low waste production, most of them in the Global North. Moreover, there are zero waste communities all over the world, as well in Asia: in Japan, Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, or Vietnam (Calvelo 2021).

The Zero Waste Approach in the Mekong Region with focus on Cambodia

There are several studies investigating the feasibility of the zero waste approach in certain countries. One study by Permana et al. (2022) looked at some parts of the Mekong region: Bangkok, Nakhon Ratchasima, Detudom, Pitsanulok (Thailand), Vientiane (Lao PDR), Phnom Penh (Cambodia) and Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam). The feasibility of zero waste concept in these countries was assessed in two steps: First, the amount of different types of waste has to be analyzed, and second, how these types of waste can be used with regard to the capacities and resources of the respective country.

The study shows that 70-80% of the waste in the Mekon region is biodegradable waste, which is best composted for the production of fertilizer or anaerobic digested to produce biogas. This is followed by 10-15% recyclable waste including plastic, papers, and steel (Permana et al. 2022). If you look at the waste distribution in Cambodia (see article “Waste Management in Cambodia”), you can see that the figures are very similar. The largest amount of waste is food and organic waste (55 %), followed by plastics (10 %) and glass (8 %), both of which are recyclable (Pheakdey et al. 2022). This means that in Cambodia composting and anaerobic digestion are possible techniques that would go a long way towards zero waste, in order to use the value of more than a half of the generated waste. Furthermore, a focus must be placed on expanding the recycling infrastructure as it accounts for the second largest amount of waste. Especially in Phnom Penh, where the amount of plastic waste has significantly increased in the last year due to the rise on single-use plastic such as packaging.

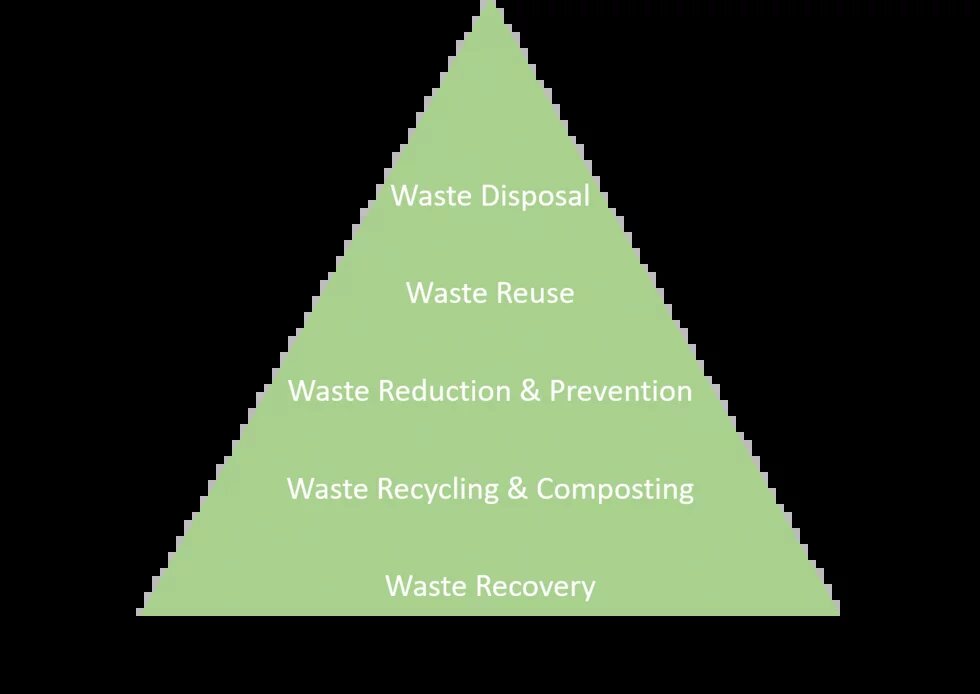

Secondly, one can also rank the techniques for zero waste approach that are best to implement in terms of capacities and resources of the country itself, such as financial investment and technological knowledge. The hierarchy, which range from the easiest to implement with little capacity and financial investment (but unsustainable), to much required skill and investment, but (sustainable) towards a zero waste approach, is as follows: (1) Waste Disposal, (2) Waste Reuse, (3) Waste Reduction and Prevention, (4) Waste Recycling & Composting, and (5) Waste Recovery.

Own illustration based on waste management hierarchy from Permana et al.

It is easy to understand that waste disposal in landfills is the easiest handling system. This explains why most of the waste in the Mekong regions goes to landfills (44% of the waste in Cambodia is disposed on landfills), but the sustainability aspect is not taken into account here and is therefore not a variant in the direction of zero waste. Waste reuse is also very simple, because if you reuse your waste it does not need to be disposed. However, it depends on the customs and culture of people and especially the knowledge of how to reuse specific waste. No involvement of technology and investment is needed, but awareness rising. The same with waste reduction and prevention. It is the best way to achieve zero waste because it limits the negative impact in general because no waste is produced. It depends on the lifestyle and social construct of the nation, which means no huge financial investments and advanced technology are needed. However, citizens awareness and knowledge is needed (Permana et al. 2022). With regard to Cambodia, a study from 2020, shows that lack of information and poor knowledge are main indicators for not reducing the consumption of plastic bags (Ing 2020). Nevertheless, the environmental awareness of the young generation of Cambodia is not to be underestimated as the interviews with zero waste projects confirm (see article “Best Practices: Pioneering Zero Waste in Cambodia”). Recycling waste is a significant element towards a zero waste approach, as recyclable waste is the second largest type of waste. Here, advanced technology is not necessarily required, but recycling on a large scale requires high financial investments. The focus here should be on the recycling of plastics, as these make up a large proportion of waste in the Mekong region, as in Cambodia, and most polymers are also quite easy to recycle in terms technological procedure (Permana et al. 2022). The same is said in another study on Cambodia. The private sector needs to be encouraged by the government to invest in domestic recycling infrastructure (Pheakdey et al. 2022). Moreover, composting waste is a cheap and easy way to turn waste into something useful. Natural fertilizer can be produced, which binds moisture, reduces plant diseases and avoids pesticides. The problem is that composting is limited in terms of the capacity required and thus cannot handle the whole amount of food and organic waste. Composting is rather something for a single consumer and therefore rather a by-product to achieve zero waste. A project in Phnom Penh, supported by hbs Cambodia, demonstrates it. Compost City (introduced in article “Best Practices: Pioneering Zero Waste in Cambodia”) is a project that set up a home kit to compost household waste. Besides the infrastructure investments, recycling and composting, requires awareness raising in terms of segregation of waste is necessary. Since composting alone is not enough to handle the whole amount of organic and food waste generated, waste recovery is a further technique, which leads closer to the zero waste approach. However, the transformation of biodegradable waste into energy needs large capital. In three cities in Thailand, including Bangkok, biogas systems for electricity generation and for the supply of cooking gas do exist. In Cambodia and Laos, meanwhile, it is still in the feasibility study stage, according to Permana et al. (2022). The study by Pheakdey et al. sees the potential for waste recovery in Phnom Penh due to the high volume of waste, but notes that the high wet content of waste in the rainy season is challenging and requires advanced technology. Subsidies would therefore be required and this is still lacking in Cambodia. A cheaper alternative would be to convert waste into Refuse Derived Fuel, which is used to replace cement. There is already a cement company in Kampot that uses this technology (Pheakdey et al. 2022).

Conclusion: Zero Waste for Cambodia?

While the realization of the zero waste approach in Cambodia remains a work in progress. The main principles of the approach such as reduction or recycling is far from reaching its full potential. These principles are not yet fully implemented, however there is already notable acknowledgment and engagement with some components of the waste hierarchy. Progress in waste reduction, reuse and prevention has been underlined by initial research studies examining, for example, the factors that influence behavioral change. As mentioned in the first part of this article, research is part of the collaborative zero waste approach. The government's "Today, I don't use plastic" campaign further signals a step towards zero waste by promoting reduced plastic usage. However, challenges persist, particularly in establishing the mentioned domestic recycling industry. Despite the 3R strategy introduced by the Ministry of the Environment in 2008 and a task force on plastic waste established in 2019, effective implementation is crucial for a large-scale impact. Local recycling initiatives, such as “Trash is Nice” (see article “Best Practices: Pioneering Zero Waste in Cambodia”), though commendable, are insufficient in themselves. Similarly, the potential for composting, rather an option considered for individual consumers, requires government support through subsidies to achieve broader success, which a single project like the Compost City (see article “Best Practices: Pioneering Zero Waste in Cambodia”), cannot achieve alone. In the realm of waste recovery, the establishment of the national committee for the promotion of energy recovery from waste in 2021 holds promise. The hope is that this committee will incorporate subsidies and set forth more favorable framework conditions for Waste-to-Energy (WTE) projects, contributing to the holistic realization of the zero waste Approach in Cambodia. In essence, while challenges persist, there is a foundation in place. Particularly at the civil society level as represented in article “Best Practices: Pioneering Zero Waste in Cambodia” the foundations are layed. These can be enhanced through concerted effort from the government through policies in support and effective implementation of waste management strategies on a national scale.

References

Awasthi, A.; Cheela, S.; D’Adamo, I.; Iacovidou, E.; Islam, R.; Johnson, M.; Miller, R.; Parajuly, K.; Parchomenko, A.; Radhakrishan, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, C.; Li, J. (2021): Zero waste approach towards a sustainable waste management. Resources, Environment and Sustainability 3 (100014).

Calvelo, J. (2021): Zero Waste Cities of Southeast Asia. Online Available: https://www.breakfreefromplastic.org/2021/02/11/zero-waste-cities-of-southeast-asia/. Last updated: 01/12/23.

Ing, K. (2020): Factors influencing the reduction of plastic bag consumption in Cambodian supermarkets. Cambodia Journal of Basic and Applied Research 2 (2), 122–155.

Permana, A.; Bhandari, B.; Ovhal, N. (2022): The Engineering of Zero Waste: Between Sustainability and Waste Production. Innovative Engineering and Sustainability 1 (1), 38-49.

Pheakdey, D.V.; Quan, N.V.; Khanh, T.D.; Xuan, T.D (2022): Challenges and Priorities of Municipal Solid Waste Management in Cambodia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (8458).

Sang-Arun, J.; Kim Heng, C. (2011): Current Urban Organic Waste Management and Policies in Cambodia. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies. Online Available: http://www.jstor.com/stable/resrep00882.8. Last updated: 29/08/24.

Interviews: Best Practices: Pioneering Zero Waste in Cambodia

As the previous article illustrates, there are opportunities to make waste management more sustainable with the zero waste approach. Although the full realization of zero waste in Cambodia requires government investment in large infrastructure projects as well as subsidies for private companies, individuals at the community level are already pioneering the path towards zero waste. This article reveals the stories of individuals in Cambodia dedicated to leaving a positive environmental impact through waste prevention or recycling. The stories are based on interviews conducted by the author in October 2023. The stories of the individuals, who were partly supported by hbs Cambodia, aim to showcase active citizenship that is essential for a sustainable future in the country.

Logos of the zero waste projects interviewed.

Only One Planet Cambodia: A Registered Business with an NGO Heart

I had the chance of sitting down with Sandy, an American, living in Asia for over 22 years who founded “Only One Planet Cambodia" in 2018. As we met at her latest initiative, an eco-shop called Be Eco!, adorned with a selection of organic and sustainable products from local brands, she recounted her journey and the challenges she's faced along the way. Inspired by a friend, who was tackling the problem of single-use plastic by importing eco-friendly alternatives, she founded “Only One Planet Cambodia” for selling containers, crafted from compostable sugarcane while embodying the principles of biodegradability and environmental friendliness. An alternative that protect the environment while providing convenience to consumers. Structuring the endeavor as a company was a pragmatic decision. At that time, Cambodia's government was gradually tightening restrictions on civic space, making fundraising and registration as an NGO increasingly complex. Faced with this dilemma, Sandy chose to register her venture as a business. She has also created a website to help businesses and individuals learning about the issues, and find resources to take eco actions in Cambodia (www.eco-business-cambodia.com). Through this portal, consumers are encouraged to support Cambodian businesses that take steps to reduce their waste/plastic use, as well as find locations in their area for recycling, water refills, etc. They also manage a community glass recycling programme in Phnom Penh with local food and beverage partners as collection points (over 40,000 kg collected for reuse/recycling so far). Be Eco! was created as a non-profit collective of small businesses that are committed to producing/providing products that reduce packaging waste, and/or offer natural/organic products. The shop also acts as a community ‘eco hub’ where consumers can drop off their recycling, and as a liaison with local vendors for repairing a variety of items such as small appliances, shoes, clothing, and luggage. Workshops and environmental trainings are offered periodically at the shop. The entire idea is to support small businesses that are socially and environmentally responsible. In addition it fosters a community that creates opportunities and makes it easier for everyone to do more. On top of that, they organize EcoDrinks every last Thursday in the month, a gathering at different eco-friendly restaurants where like-minded individuals come together to discuss, share ideas, and collaborate. These events are shared on both the Eco-Business-Cambodia and Only One Planet Facebook pages and everyone is welcome to join. Sandy emphasizes the importance of unity in tackling environmental issues. By pooling resources and working together, greater progress can be made. One ingenious idea in the works – in collaboration with Irina of Bong Bonlai Vegetarian Restaurant - is the creation of party boxes containing plates, cutlery, glasses, and more that can be rented for private home parties, reducing the need for single-use plastic tableware, with any profits supporting a local animal shelter. Yet, the road is not always easy. Sandy admits that the shop is not very profitable and demands considerable personal energy for tasks like management and maintaining an online presence. Initially, they attempted to provide “Repair Fairs” for recycling, refurbishing, and reusing items, at the shop which included services like knife sharpening, shoe repair, and watch repair, performed by local businesses. While a noble endeavor, the return on investment was lacking, especially for the local vendors. That is why they switched to function as a drop off point at Be Eco! Further challenges persist, including a high turnover of partners, particularly among expats, who often leave the country, causing projects to halt or end. Moreover, there is the lack of detailed environmental awareness in Cambodia, which leads to various cheaper, greenwashing products that divert sales away from true solutions. Nonetheless, Sandy remains hopeful, seeing the potential for change in Cambodia's youth. She firmly believes that the younger generation can transform the world with their commitment to environmental sustainability. Until then, she continues to run Only One Planet Cambodia, a registered business with a beating NGO heart, to make a positive impact for her environment and community.

Eat or Not to Eat: Daily Choices for a Sustainable Future

The Youth Resource Development Program (YRDP), a partner of our foundation, is on a mission to empower the country's youth by promoting critical thinking skills, amplifying their civic and political rights, and fostering a sense of social responsibility. Lyhorng is a project assistant for youth engagement in policy at YRDP with the focus on climate change and the extractive industry. In 2023, they embarked on a campaign, both online and offline, centered on the theme of zero waste. Their online campaign revolves around sending advocacy messages to the government, coupled with an engaging competition. The challenge was simple: post content on reducing plastic waste and the student with the most comments wins. As a further vital part of their online campaign, YRDP created informative videos on the 4 R campaign: reduce, refuse, reuse, and recycle. They also posted videos of interviews with people who discussed their daily battle against single-use plastics. The online campaign captured approximately 260 energetic youth. However, YRDP's work is not confined to the digital realm only. The offline campaign took place in Siem Reap and Phnom Penh through workshops. This time, they invited speakers from an array of relevant stakeholders, including government officials, private sector representatives, and dedicated NGO members. Their approach remains the same—to bridge the gap between the youth and the authorities, enabling young voices to directly address the government and demand regulatory improvements. This can take many forms, from eloquent written statements to the power of music. Have there been tangible successes already? Lyhorng cannot provide a definitive answer, but what is clear is the impact of the campaign in raising awareness about the effects of plastic and offering practical ways to reduce plastic usage. The challenges, she acknowledges, are in reaching young people, who often juggle their participation in YRDP programs with their school commitments. For Lyhorng, the key to progress lies in the government's implementation of existing laws and regulations. Many people only see the issue in plastic bags, oblivious to the ubiquity of plastic in everyday items. She emphasizes the significance of knowledge and education—like many others, she first encountered environmental issues at university and not before in highschool. However, she also recognized that it is not just about awareness; action matters. Lyhorng is aware that reducing plastic in her daily life is important but can be a challenge. There are moments when it comes down to a simple choice: eat or do not eat. It is these daily choices when you are in the city and you are hungry, whether to get something to eat quickly wrapped in plastic or not. You always have to be prepared. It is about the collective efforts of young individuals like Lyhorng that want to set Cambodia on a path toward a plastic-free, sustainable future.

Making the World More Sustainable, One Slice at a Time

In Phnom Penh exists a place where pizza is not just about satisfying your taste buds, but also about making a positive impact on the world. 4 P's has a mission that goes beyond just serving delicious stone-baked pizza. I recently had the pleasure of sitting down with the manager of the BKK1 restaurant to delve into their commitment to the concept of zero waste. At 4 P’s Zero Waste begins with their food sourcing, where they collaborate with various partners who share their commitment to sustainability. From the moment ingredients arrive at their kitchen, a meticulous process is set in motion. The kitchen staff ensures that food waste is minimized through innovative approaches: Vegetable scraps are sent to local farmers, who use them to feed tilapia, which ultimately ends up as a pizza topping at 4 P's. Leftover pizza dough is used to feed crickets, and the resulting cricket powder is purchased by the restaurants. However, what happens to the waste that can't be avoided? That is where 4 P's true genius shines. They have established zero waste rooms within their restaurants, where waste is meticulously sorted into 15 to 20 categories. This waste is passed on to partner organizations that can turn it into something useful. For example, plastic waste goes to Trash is Nice, who recycle it. But the journey towards zero waste doesn't end in the kitchen. 4 P's believes in raising awareness and fostering a sense of responsibility among their employees and customers. Monthly meetings are held with the staff to discuss waste amounts and disposal methods, with the goal of changing habits. For their customers, 4 P's opens their doors to workshops that introduce the zero waste concept, allowing for open discussions and tours of the restaurant, including a peek into the world of their zero waste room. The restaurant itself is a testament to their commitment, with everything from the decor to the bill folders crafted from recycled materials. Moreover, 4 P's goes a step further. They act as intermediaries between waste generators and recyclers, making it easy for people to drop off their waste, which 4 P's then takes care of, ensuring it's properly recycled. They are even considering expanding this initiative to include small street restaurants and coffee shops, recognizing the potential for these establishments to become vital recycling hubs. According to their own zero waste report, 4 P’s managed to recycle 91.1% of their total waste, with a mere 8.9% being sent to landfill. This is a remarkable achievement and add to that the amount of people they have already reached. 4 P's has turned pizza into a force for good. By making the world more sustainable, one slice at a time, they have set an example of what can be achieved when a restaurant combines culinary excellence with a passionate commitment to a better, more sustainable world.

Cambodia's Zero Waste Pioneer

Meet Sochenda, the environmental content creator with a mission to inspire responsible consumption and climate action through her vibrant presence on various social media platforms. Whether it is Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, or YouTube, she leverages them all to spread her message. With her channel called ZEROW, Sochenda has become known as the "Zero Waste Pioneer of Cambodia," with a loyal following of around 78,500 strong. Her journey embarked in 2018 when she began documenting her personal transition toward a zero-waste lifestyle. What began as a simple desire to reduce her own environmental footprint expanded to cover various facets of eco-friendly living, climate action, and clean energy. Sochenda's videos capture the essence of her journey, from buying a whole chicken and carrying a large pot to avoid plastic packaging, to using apple cider vinegar as an alternative to conventional shampoo, or demonstrating ways to remove labels from glass jars. These videos on practical zero waste living topics resonate deeply with her audience, because it addresses everyday topics that people can readily relate to and understand. The less tangible concepts for many, such as climate change and carbon footprints, does not resonate so well, she noticed. However, Sochenda knows about the urgency of climate change and the importance of reducing carbon footprints, that is why she wants to focus more on these crucial topics in the future. In addition to her digital presence, Sochenda owns a store, called “Zerow Station”, where she offers a range of eco-friendly products, complete with a refill station. Her commitment to providing access to eco-friendly products and refills is a testament to her belief that making sustainable choices should be accessible to everyone. On top of that, she also has other projects in collaboration with hbs Cambodia. During our interview, Sochenda notes the government's recent campaigns on raising awareness about plastic waste and promoting ecotourism via social media platforms. She also commends the positive changes in Phnom Penh's waste management system, particularly the separation of collection services among three companies. However, she emphasizes that more work is needed, especially in implementing systematic waste management that includes a separation system and the formalization of the livelihoods of waste pickers. Sochenda's journey is not without its challenges. Living a zero waste lifestyle within a family where not everyone shares the same commitment, especially within the same household, can be demanding. Financial hurdles also arise, as monetizing social media platforms presents challenges due to Cambodia's limitations, such as restricted access to certain features and revenue streams. Despite all the challenges to get grants and in-stream ads, Sochenda sees the opportunity to offer video production services for NGOs and companies and enable clients to spread their sustainable messages through the videos. In general, Sochenda is undeterred. The positive feedback, recognition, and respect from her audience serve as a powerful motivator. Every day, people watch her videos and embark on their own journeys of transformation, making small but impactful changes in their lives.

Waste Consultation: Pioneering Waste Reduction and Management

As the founder of Little Green Spark, Sarah Kolbenstetter has embarked on a mission to guide businesses and organizations in Cambodia toward reducing waste and managing it more efficiently. Her approach is clear: raise awareness, provide training, and offer waste auditing services, all aimed at tackling waste reduction at its core and most significantly, to prevent waste from happening in the first place. The intervention to implement a zero waste project typically span one to two months composed of four pivotal phases: the initial assessment phase, the planning phase, the implementation phase and the monitoring phase. During that intervention, she trains the staff, establishes waste sorting stations, forges connections with local recyclers, and develops project management tools, such as an action plans, a monitoring plan and a waste management S.O.P. In this endeavor, she collaborates with an array of partners, including local recycling companies, or projects such as Compost City. One of the significant challenges Sarah faces is the lack of communication within her client companies. Often, she is initially hired by management, but the staff was not fully involved from the beginning. To bridge this gap, she encourages clients to establish a waste committee, a forum where everyone is held accountable, from the office cleaner to the management. Her clients hail from diverse sectors, including factories, local and international companies, schools, and renowned international organizations such as GIZ. Some companies grasp the concept of waste reduction once they recognize the benefits it can bring such as improvement of their band image, employee engagement as well as diversification of their client base. In contrast, schools, they often serve as enthusiastic participants in this transformative journey. In the context of Cambodia, Sarah acknowledges the progress made in waste management. Bins line most streets, and landfills are gradually evolving to meet international standards. Yet, there is a crucial need for the separation of organic and non-organic waste, and recycling infrastructure remains relatively insufficient. Sarah's advice for small coffee shops that cannot afford changes to non-plastic alternatives financially to take the simple step of asking customers if they truly need all the items from plastic cups, straws, or bags. This small shift can go a long way in reducing waste at the source. In her personal life, she has adopted a largely zero waste lifestyle, but she admits she sees the daily challenges that come with it like giving up some products that she enjoys, like cheese and ice cream.

With the Lucky Number Towards a Greener Tomorrow

At Eleven One Kitchen, a Khmer restaurant, it is not just the flavors that set this place apart; it's their unwavering commitment to reducing plastic usage and making a little difference in the world. The driving force behind this mission is the restaurant's owner, whose passion for waste reduction was ignited during her earlier days at another restaurant where her boss inspired her to care for the environment. Srun Soklim, the owner, decided to initiate small changes, and the response was overwhelmingly positive. Witnessing the enthusiasm around her, she knew she had to continue her journey towards a more sustainable future. Today, Eleven One Kitchen proudly serves its dishes in biodegradable food packaging, minimizing straw use (even biodegradable ones), and raising awareness about plastic usage among their staff and suppliers. She arranges training sessions with Plastic Free Cambodia for her staff. One of the most impressive aspects of Eleven One Kitchen is their catering services, which are entirely plastic-free. However, this commitment comes at a price, with the need for additional staff for transportation and cleanup. She willingly invests in the environment, even if it means higher costs, knowing that it is a step towards making the world a better place. She understands that not everyone can make the same leap, particularly smaller coffee shops that must carefully balance profitability and the lack of affordable alternatives to plastic. What becomes evident in conversations with her is that this is a journey, both for her restaurant and her personal life. She openly acknowledges that reducing plastic usage is not always easy, but she strives to make daily improvements. Her most significant challenge lies in convincing others to adopt similar practices, and she calls for more government responsibility, particularly in schools. She points out the inconsistency of promoting plastic-free living to children while plastic is used extensively at school events. In her restaurant, challenges include addressing ignorance, complaints about the inconvenience of avoiding plastic, and resistance from certain individuals. Moreover, they are still working on addressing food waste due to logistical challenges. However, her team remains creative in their approach. For example, they serve Khmer fried roast chicken in passion fruit bowls instead of small plastic containers. Lastly, the name of the restaurant holds a special place in her heart. She married her husband in November, and her first daughter was born on November 1st, making "Eleven One" a lucky number and a constant reminder of her commitment to making the world a better place, one plate at a time.

Crafting Hope and Change from Plastic Waste

After a tour through the tiny but gleaming recycling workshop of Trash is Nice, I had the privilege of sitting down with the passionate individuals behind this endeavor. They shared their story, their challenges, and their dreams of transforming plastic waste into something beautiful and meaningful. It all started five years ago when Alix set up a recycling facility in a small village near Kampong Cham, complete with a trusty shredder, and began her journey towards combating plastic waste. Later, she relocated to Koh Rong Sanloem, where she worked with a small team of four establishing a modest recycling station on the island. However, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, their project had to be put on hold. The turning point came when Alix, through the platform "Precious Plastic," a global network of like-minded individuals committed to tackling plastic waste, crossed paths with a like-minded person. Elora, who had already been running her own recycling station in France, had plans to volunteer in Cambodia. Their meeting marked the beginning of their partnership. Since May 2022, they have been operating their workshop (which they largely constructed themselves) at Trellion Park in Phnom Penh. They receive plastic trash from various sources and transform it into soap trays, coasters, hair combs, flowerpots, and carabiners. Beyond crafting beautiful, eco-friendly products, they are committed to spreading awareness about plastic pollution. They conduct workshops for schools and groups of adults, using a variety of approaches involving hands-on recycling, crafting, and some delve into the engineering principles behind their machines. In their workshops, they use material from hbs to visually explain the problem of plastic waste. They even offer workshops in the local Khmer language, often with the assistance of a translator. Their efforts have not gone unnoticed in Phnom Penh, where word of mouth serves as their primary form of advertisement. They cannot complain about the amount of plastic waste they get, and they have even received requests from larger companies searching for solutions to manage their plastic waste. However, they remain dedicated to their small-scale recycling, which allows them to preserve the value of plastic through their craftswomanship. Yet, they admit that their greatest challenge lies within their own mindset. The journey is personally demanding because of the minuscule impact within the global plastic pollution crisis. Also financially, it is a challenge since for now, the sale of these products only sustains their operation, covers the rent and the salary of their Cambodian workplace manager. Their dream? To see more workshops like theirs established in other provinces of Cambodia, forming a network of individuals who cherish and champion the potential of plastic.

One Non-Plastic Straw Can Change the World

Lot369, a café with a vision that goes beyond just serving coffee and food. It is a place where conversations flow as freely as the brew, and where a single, non-plastic straw can symbolize a commitment to change the world. I sat down with Ravut Socheata, the cafe's manager, and her assistant, Reth Chanrath, to uncover the story behind the café. The café's owners, a couple from Australia, have made it their mission to reduce plastic waste and initiate change, but it is not without its challenges. They have explored various avenues, and it has not been a smooth ride. They started by offering paper boxes for takeaways. However, it was not long before customers began voicing their concerns. "How should motor scooter drivers transport their coffee or food without a plastic bag?" they asked. Then it came to the decision to stop selling plastic water bottles, replacing them with water in glass bottles. This too faced resistance, with some customers worrying about cleanliness due to reuse. The transition to steel straws was not any easier, as many customers still preferred paper or plastic straws, despite the staff's best efforts to highlight the proper cleaning process. They experimented with paper containers for sauces, only to discover that the sauces would leak out during delivery, prompting a return to plastic containers, albeit with a commitment to minimize their use. Socheata notes that Cambodians have not traditionally grown up with a strong sense of environmental awareness, making it challenging to change behaviors. While there is a shift happening with the younger generation, customer comfort remains a priority. Charging fees for food packaging, for example, was considered but ultimately dismissed to avoid driving customers away. Instead, they try to motivate their customers through incentives, such as offering a discount on coffee for those who bring their own cups. Waste separation has not been a focal point within the café itself yet, because of the non-existence of any further state separation system. However, they have found creative ways to make a positive impact, such as collecting coffee grounds and offering them to customers for their plants. Similarly, empty cans are gathered and provided to waste pickers. According to the manager, waste management in Cambodia should align more closely with countries like Korea, with scheduled waste separation and stricter penalties for non-compliance. They believe the government should promote these initiatives on television, as it remains a primary source of information for all generations, particularly the elderly. In their journey towards sustainability, the café collaborates with environmentally conscious suppliers like Only One Planet, who provide plastic-free coffee cups, and Dorsu, who supply napkins. With other suppliers still in transition to be plastic free, any plastic received is reused, often as garbage bags. The journey is also a learning process. Socheata recalls a time when she purchased a package of plastic straws for her employees. Her boss responded by sending her about 20 links about zero waste, urging her to read them. That moment was the turning point. She realized that if everyone could avoid just one plastic straw a day, it could change the world.

The Tale of Compost City

Monorom stands as the founder of Compost City. It is a venture that she ignited in 2019 when she emerged victorious in a competition hosted by Impact Hub Phnom Penh, a win that marked the beginning of an environmental journey. After the initial spark of winning the competition, she found herself at a crossroads. Did she want to become a manufacturer of compost kits? It was a pivotal moment of introspection. Monorom had embarked on this path to reduce her waste and energy consumption, one step at a time. She began by adopting simple changes like having her own shopping bags and containers, saying no to straws, flyers, or business cards and making her own body and hygiene products, which significantly reduced her general waste. The only remnants were her food waste. And so, the idea of the compost box took root. A kit for the production of compost from kitchen waste. However, Monorom's vision extended beyond manufacturing kits. She sought to share her knowledge, to spark discussions, and to engage with people. Hosting workshops became her true calling. Her quest to understand composting led her into the intricate world of ecology, where she explored the vital roles played by microbes, the nutrient cycle, and more. Monorom also understood that for people to truly comprehend and appreciate the point of composting and the importance of understanding soil and organic matter to tackle environmental issues, they needed to feel it, to touch it. This realization birthed the concept of an educational garden, a space where the beauty of interactions among living beings and elements could be shown live and on-site. In this garden, different observation trails would allow visitors to grasp ecological concepts like photosynthesis, decomposition, succession, symbiosis. Workshops conducted in the garden have begun to shape minds, but it's a realm still in the research and development phase. Monorom's commitment to environmental awareness extends beyond the realm of composting. Every Wednesday, she arranges movie nights at the hbs office, as Compost City is also a partner of hbs. The film screenings delve into various topics related to the environment. Post-screening, neighbors and attendees partake in discussions over a meal generously sponsored by HBS. For Monorom, documentaries have been life changing. For her, they reveal the hidden truths, exposing the power dynamics that shape our lives. It was in France, while watching documentaries like The World According to Monsanto or Food Inc., that she grasped the reality — she was living in a society that prioritized exploitation and accumulation over humility and sharing. Monorom's greatest challenge in her work, as she candidly admits, is translating her vivid vision into a tangible reality. It is a process of self-discovery and self-confidence. However, with the support of her three dedicated partners who share her vision, she has found renewed strength to push the project forward.